Note: This is my annual New Year’s post where I think out loud about the trendlines of history and what the future might hold. It touches on economics, geopolitics, war, and history. If these things don’t interest you, move along now before things get interesting–or, uninteresting, as the case may be.

I’ve been a student of history since before I could learn to read–and because of my love of history, I’ve spent most of my life flip-flopping between two equal and opposite extremes: a desire for a quiet life in a peaceful world, and a yearning to see history unfolding in front of me and all around me, and perhaps to have the opportunity to take part in it.

After all, World War 2 and the 1960s and its attendant madness were over before I was born. The Cold War ended before I hit high school. History was over, and I’d only ever gotten to see the tiniest little bit of it first hand.

Sure, there was terrorism, and the World Trade Center (twice), and little wars here and there, but, generally, the world wasn’t the kind of place it used to be, and that was a good thing.

That was then.

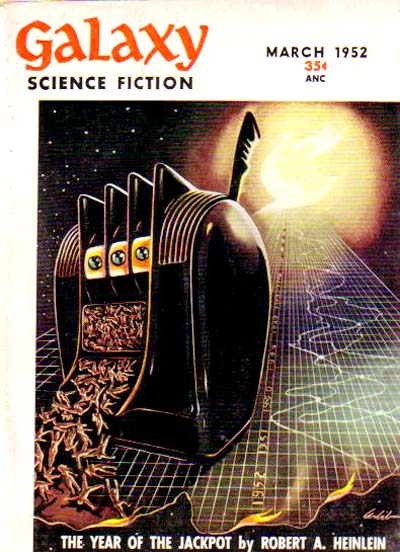

Back in 1952, Galaxy Science Fiction published a story that posited that history was governed by dozens of metahistorical cycles–the rise and fall of civilizations, the periodic rise in insanity curves, sunspot cycles, the business cycle,  etc.–all of which came to a major peak or major trough in the same year, The Year of the Jackpot (you can now read it as part of this collection of stories by Robert A. Heinlein). When I first read it, I thought it was a fun satire on the whole notion of cyclical history first pioneered by Polybius, which seriously fell out of favor when The Cold War and the industrial revolution seemed to change the whole nature of history. Only throwbacks and retrograde nostalgics seriously thought history was cyclical anymore.

etc.–all of which came to a major peak or major trough in the same year, The Year of the Jackpot (you can now read it as part of this collection of stories by Robert A. Heinlein). When I first read it, I thought it was a fun satire on the whole notion of cyclical history first pioneered by Polybius, which seriously fell out of favor when The Cold War and the industrial revolution seemed to change the whole nature of history. Only throwbacks and retrograde nostalgics seriously thought history was cyclical anymore.

That was then.

This is now:

2017 was The Year of the Jackpot. Or, more accurately, the first year in the Era of the Jackpot.

I said last year that every disruption has a cutting edge and a bleeding edge. The bleeding edges of the great disruptions of my youth (the fall of the Soviet Union, the rise of the Internet, biotechnology, hydraulic fracture drilling, and the great population contraction) are all coming to their peaks and troughs at the same time, and the great cycles of history that really are there (the business cycle and the generational cycles that swing the pendulum of civilizations) are all hitting at the same time.

I’ve talked about the consequences of some of these things over the last few years, in last year’s New Year’s post, my two posts on Brexit, but here’s the basics of what’s going on:

Almost everything in the world that you’re familiar with exists in the form it does for three reasons:

- The industrial revolution meant that more could be made with less if you centralized production

- Based simply on their geography, most countries in the world cannot exist with modern conveniences and necessities unless they are hooked into a global trade network. From medicine to fresh fruit to gasoline to electricity, all wealth is secured through international trade.

- Global free trade meant that supply chains could hyper-specialize and every single piece of every single gadget, device, foostuff, article of clothing, luxury, and machine could be made in the one place in the world that was best suited to make it. This means, for example, that the supply chain for the iPhone (from the minerals it’s made from to the final device in your hand) is thousands of steps long. Each of those steps provides hundreds-to-thousands of people with the jobs and income that their lives depend on. Powerful central governments only exist because of these kinds of economies of scale.

The world we know–its material wealth, the aggressive reduction in poverty over the last 30 years, the generous welfare state enjoyed in most of the developed world, the reduction in birth rates and disease, the empowerment of women, the lessening of racial and ethnic barriers, etc.–all depends upon these three basic facts.

Everyone on the planet under the age of 80 has grown up knowing no other world than the one I’ve outlined above.

But now, that world is ending.

- Localized manufacturing, 3D printing, and access to information (thanks to the Internet) is re-localizing industry–which is causing huge problems with governments around the world as they struggle to maintain control and order in a system that no longer looks like the system they were designed to govern.

- The wealth generated by international trade has allowed countries like Japan, China, South Korea and large swaths of Europe to develop and/or recover rapidly post WW2 (or post-inclusion in the international trade order), without having to sink much money into their own military complexes. This makes them attractive targets for belligerent up-and-coming powers, which is a problem becasue…

- Global supply chains depend on the ability to ship goods long distances for low prices, with little-to-no risk of piracy. Since 1948, this system has been guaranteed by the US Navy–a good deal for everyone. The Americans needed allies in the Cold War, and most other countries needed international trade. But the Cold War is over, and, now that America is energy independent, the Americans don’t need international trade (economically speaking). The Americans are now withdrawing from the seas, and the power vacuum they’ve left is setting the stage for major international wars that are will knock up to 80% of the global supply chain off line for long stretches of time.

On top of that, mixed welfare-state economies are predicated on the notion that every generation will be bigger than the one before it, so that the young and middle age workers will pay the pensions of the retirees. Consumer-led economies are predicated upon the middle-aged workers loaning money (through banks and investments) to younger workers who are bootstrapping their lives. The birth control pill, while it has put paid to fears of overpopulation, has now thrown most of the world into terminal demographic decline–financial collapse is on the horizon (or in progress) for most countries in the world. Where it’s not, American withdrawal means that those countries in Europe and Asia who depended on America for their national defense (which was most of them) are suddenly re-militarizing so that they can defend themselves as America loses interest.

And America has lost interest. Since the end of the Cold War, we’ve elected the less internationally-minded candidate in every single election. Now that we don’t need the rest of the world to fight the Cold War, the thinking goes, why should we spend so much of our time and treasure protecting everyone else?

The problem for the rest of the world is that, without a disinterested hegemon to play referee, the world will be a much more volatile place. And we’re already seeing it play out in three major areas across the world.

I wish I could offer words of comfort on this point, but I can’t. It will get worse, maybe much worse, before it gets better.

Because America has another problem–a predictable, regular one. Our two-party system is formed out of alliances that made sense in a given world. The one that I grew up with was created to handle the problems of a Cold War world. As soon as the Cold War ended, the viability of the two-party system expired. This new world we’re in–one dominated by regional interests, new empires, unbelievably sophisticated technologies, localized power, and less international trade–is a world we don’t even have the vocabulary to talk about yet, let alone vote about. So, we’re having a culture war instead. A miniature civil war that pits neighbor against neighbor as we try to figure out what it’s going to mean to be an American in the 21st century.

If you think 2016 and 2017 were tumultuous in America, you ain’t seen nothing yet. The two major parties have now all but disintegrated, and the labels associated with them now mean nothing, and they won’t for a while. There is no such thing as a “Republican” or a “Democrat” — there are now factions of “Social Justice Democrats” and “Alt-Right Republicans” and “Traditional Republicans” and “Moderate Democrats” and a dozen other flavors of each.

The last time this happened was in the World War 2 era. It took 12 years for the parties to re-align–and it only happened that fast because there was an existential nuclear threat from the Soviet Union that snapped the party alliances together and defined the era. This time, it’s going to take longer. Maybe much longer.

And until we sort things out here at home, the rest of the world is going to have to figure out how to navigate the power vacuum we’ve left behind–because they won’t be able to predict when (or if, or how) we’ll get involved in any particular war or dispute.

But on the other hand…

On the other side of the chaos is a very bright future. The technologies that have helped to bring us to this point are not going to disappear. The printing press caused three hundred years of war in Europe before the west internalized its effects and re-balanced. We now have the ability to create and re-engineer life, to disseminate information instantly, to colonize other planets or even deep space itself, to create cheap-to-free electricity almost anywhere, to reverse some aspects of the aging process, to de-desertify grasslands using some very clever observations of natural cycles, and to feed the whole world with a fraction of the farmland we have now (which will be important as the coming wars create widespread famines, just as the Napoleonic wars did). The rhythms of history continue to throb beneath us, and they create epicycles that pull us down and push us up, but the trend-line fundamentals all still point in a positive direction. Even without a global hegemon, even without the ability (or attention span) to create political action on things like global warming, even with massive upheavals that are now killing hundreds of thousands of people a year and are about to get much much worse, the future is bright.

The greatest feature of human culture is its ability to create technologies and traditions that allow human life to thrive in adverse geography.

And the greatest effect of human tradition and technology is that it can, by steps, change the meaning of geography, or even render it meaningless.

We are now, for my money, living through the most important century in human history. History is a bloody, messy, nasty process filled with conflict and tragedy…

But it is also how we learn better, and survive better, and, if we hold our nerve, last long enough and do well enough to outlast the life of our home planet, and our own sun, and maybe even our home galaxy.

So make this year of chaos count. Make whatever effort you can to connect to people you’d normally consider enemies. They’re fighting another front in the same war you are, and loyal opposition is always more productive than demonization and calls for genocide (not to mention actual genocide).

And hang on tight. Things are about to get very, very bumpy.

–Postscript, added 23 Jan 2023–

I am now exploring the ideas in this post and their implications at length in my series “Unfolding the World.”

You can find the first post here, or peruse the whole series here.

Very interesting, Dan.

Sitting here, north of the American border, the view is similar-but-different.

I’m watching the NAFTA negotiations and PPTA fall out with interest.

t.

You and me both.

-Dan

Pingback: Raising The Drawbridge – Cameron Cooper